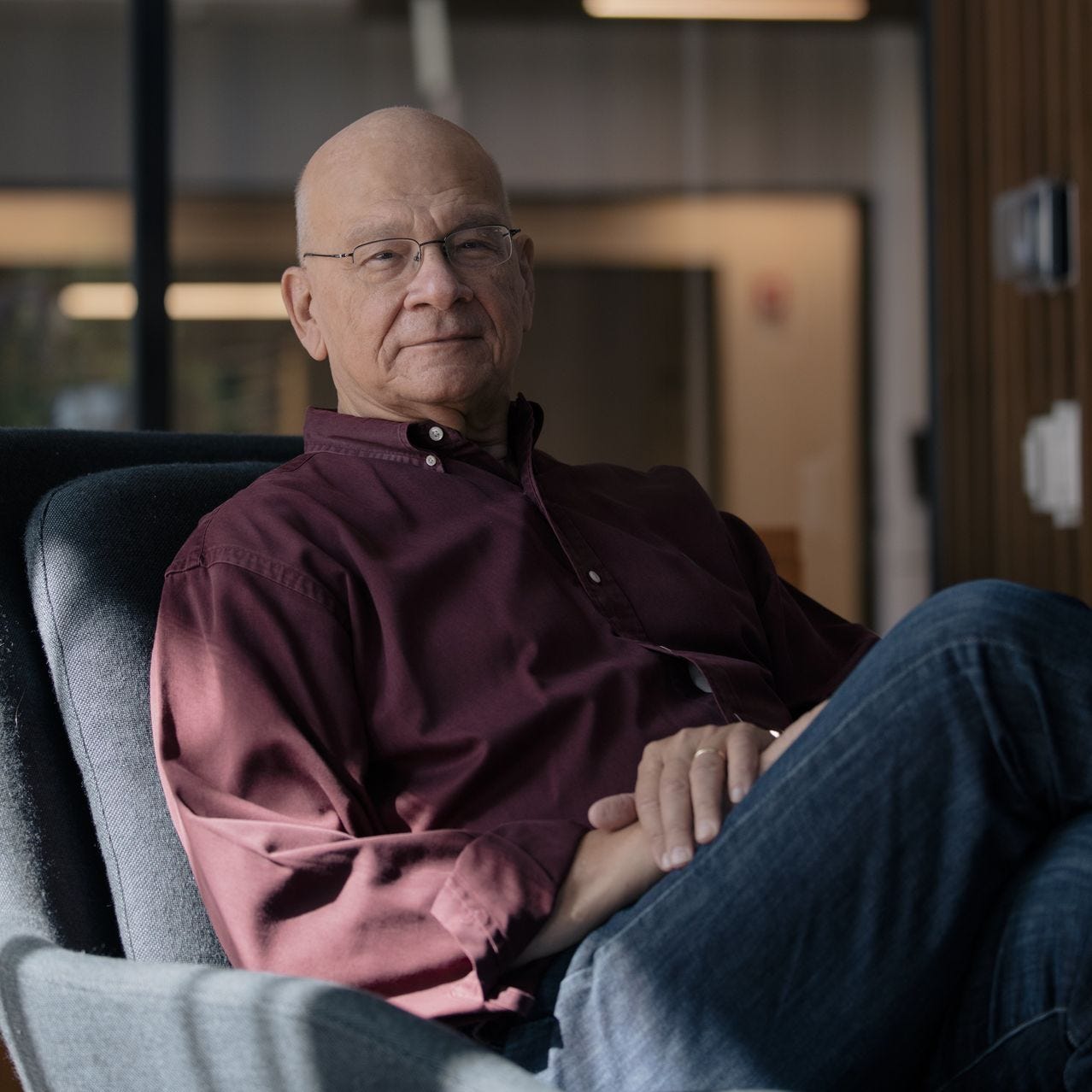

In keeping with writing what I’d like to happen upon, I write today to honor Tim Keller, someone whose faith and intellectual life I have admired for many years. Thinking about his death and reading so many moving tributes to him in the last days has led me to realize how much his life and work have shaped me in meaningful ways.

I have appreciated people’s words about him on Twitter and various blog posts, perhaps because I live in an age of disillusionment, where we can know every bad thing about everyone, and those we wish to admire leave us no shortage of bad things to find out. Keller died cleanly without scandal, leaving a legacy of building up churches, family, institutions; faith, hope, and love. Don’t hear me say that Keller was flawless or divine or superior to the rest of us. He was simply good, and wise, and generous with his gifting, and he showed many of us what that could be like through the very end of his life.

Keller’s public work and I came of age around the same time. The earliest memory I have of it is reading The Reason For God in youth group with other high schoolers when the book—his first—was a few years old. I don’t remember much of that study. The first time I remember his work pushing me in one direction or another is when I was engaged to Garrett and read Keller’s little book called The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness with a dear friend and mentor, Annie.

The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness offers a short meditation on 1 Corinthians 3 and 4 and how it interacts with the human ego or sense of self. Annie seemed to think, curiously, that understanding and caring for one’s sense of self may be advantageous to one preparing for marriage. She was correct. She didn’t likely grasp how advantageous it would be for one who had spent—always? All her former years?—performing for approval, trying to be good enough, to make up for all she lacked, to distract from her weakness and neediness, to finally address her painful sense of self.

I don’t pretend Keller’s little book fixed me or righted my upturned heart, but it so clearly and simply exposed truth at its roots. That was a particular strength of Keller: he could find roots and help me see them. And I’ve always needed that. As long as I can remember, I’ve wanted to understand what I am, what other things are, why we’re here, and what we’re for. I want deep and full explanations, good enough for sense-making and meaning-making. Otherwise, I have a difficult time.

That urge drove me to study philosophy and often directed my engagement with God. I won’t say it’s contrary to how most churches work, but it surely isn’t the normal modus operandi. I believed enough of God not to think he and this search were at odds, but I felt somewhat on my own in making it my business. When I read Keller, I found he made that search and spoke that language better than I could hope to, and it gave me a sort of anchor: someone else tied together this faith and this philosophy just like I wanted to.

As many come to find when studying philosophy and religion, understanding what is and why it is, or metaphysics, cannot long stay separate from what’s good and what it’s for, or ethics. Keller melded these like one who’d wrestled them always, and that’s what I remember finding in The Freedom of Self-Forgetfulness.

“[Paul] is saying that the problem with self-esteem – whether it is high or low – is that, every single day, we are in the courtroom. Every single day, we are on trial. That is the way that everyone’s identity works. In the courtroom, you have the prosecution and the defence. And everything we do is providing evidence for the prosecution or evidence for the defence. Some days we feel we are winning the trial and other days we feel we are losing it. But Paul says that he has found the secret. The trial is over for him. He is out of the courtroom. It is gone. It is over. Because the ultimate verdict is in.

Now how could that be? Paul puts it very simply. He knows that they cannot justify him. He knows he cannot justify himself. And what does he say? He says that it is the Lord who judges him. It is only His opinion that counts.”

Around the same time, I read Tim and Kathy Keller’s co-authored work The Meaning of Marriage. The front cover of my copy of this book lists the dates I read it, but the first one says “Engagement, Spring 2016.” This is odd given that I wasn’t engaged in the spring of 2016. Perhaps I meant the fall of 2016 or the spring of 2017. The second entry says Garrett and I read it together after we got married, and finished it in December of 2018.

In any case, to this day, it’s my first recommended marriage book. In fact, it’s one of the only books specifically on marriage or dating that I’d recommend, and I have read numerous. I do not think it’s flawless; I think it is very good.

I mainly love it because it is true and clear and lovely, like much of what Keller preached and wrote, like the God he wrote with and about. He shows marriage to be clear and lovely, like it also is. That is difficult to do because marriage so frequently gets obscured and twisted and muddied. It’s the site of much confusion and shame and hurt, and so many claiming Christ’s name participate in the desecration.

When I was entering marriage, what I wanted, like always, was to understand—to know what it is and what it’s for so I could know how to be within it. We can laugh together at a twenty-one-year-old expecting to understand marriage and find some formula for success. But like usual, she used intellect like a fishing rod, casting about for something to attach to, and she found there a picture of marriage to serve, in Shakespeare’s words, as “an ever-fixed mark / That looks on tempests and is never shaken; / …the star to every wand'ring bark, / Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken.”

The Kellers’ work stands so firm because it’s good work, yes. But also because marriage is strong in proportion to the frame of reality in which it’s rooted, and the roots of marriage grow by the stream of Christ’s gospel. They capture that clearly and lay out simple and practical explanations of what that means and how to live within it.

“When over the years someone has seen you at your worst, and knows you with all your strengths and flaws, yet commits him- or herself to you wholly, it is a consummate experience. To be loved but not known is comforting but superficial. To be known and not loved is our greatest fear. But to be fully known and truly loved is, well, a lot like being loved by God. It is what we need more than anything. It liberates us from pretense, humbles us out of our self-righteousness, and fortifies us for any difficulty life can throw at us.”

~ The Meaning of Marriage

I spent many hours between then and now listening to Keller’s sermons in the car. Most notably, I spent most all of my half-hour commutes during my first year as an 8th-grade teacher in Tim’s company. Reader, if anyone needs to hear of the all-seeing, all-encompassing love of God for herself and her neighbor, it is the first-year 8th-grade teacher.

But for the sake of space, I will skip ahead to just recently, when I read Keller’s work Making Sense of God. This book offers Keller’s second take on apologetics, or answering skeptical concerns about the faith, the first take being The Reason for God.

It’s likely the best book I’ve read written for that purpose, and again, I’ve read no few. (Would I necessarily give a secular person any apologetics book? No, but if I were looking for apologetics, this would be it.) If Keller’s first strength was finding roots, his second was exposing them in a way that met the real needs of the real people of his cultural moment, including me. Oftentimes this skill landed Keller in hot water with those who claimed he over-contextualized, or capitulated, or softened The Truth™ to cater to the culture.

I disagree and have no interest in spilling ink over the conversation, but I’d like to tell you one thing Keller did not do that many apologists do badly, and one thing he did do that’s a mark of the best thinkers and arguers.

First, Keller could give a defense that was not defensive. What I mean is that, unlike a vast swathe of Christian Thought, he did not act or interact like a defender of Christ’s Alamo. He acted and interacted like a friend and child of a very present, very coming King. As such, he offered reasons from a place of complete confidence. I have always thought it odd when Christians of any stripe enter conversations nervous, angry, combative, or any other attitude that isn’t quiet confidence working in love. One’s attitude, in my humble opinion, is always the first apologetic. What kind of God could an outsider possibly consider whose emissaries seem so frantic? Why does he need so much protection?

Keller did not have a God who needed protection; he had a God worth proclaiming and delighting in. Because of this, I think, he was able to do the second thing, the thing good arguers do, to a masterful degree.

When I teach my freshmen argumentation and fallacies at the beginning of a semester, I go out of my way to emphasize and re-emphasize the straw man fallacy. Fallacies are mistakes in argumentation, and this mistake argues against a weakened or falsified version of an opponent’s position. But more than just understanding this pitfall, I want them to think of not committing straw man fallacies as a framework for argumentation. When we engage an argument, we engage a person who’s an arguer. Persons demand respect. We also search for truth. Truth demands respect. What we don’t do is anything we can to win: that endeavor leads us to disrespect persons and snub truth, and both of these are vices. Winning aims mostly at consoling or congratulating ourselves.

The best ethos for argumentation is really a counter to the straw man: the steel man. That method asks how I can find the strongest possible version of my opponent’s position to address, even how I could personally improve it. That’s where I most often found Keller’s arguments. For a quick fact check on that, look over the references sections for his books: you’ll find sociologists, philosophers, New York Times columnists, historians, scientists, politicians, celebrities, and more. Among them will be people who disagreed with Keller in all manner of ways.

I have always been grateful that Keller, the pastor and religious author, read more philosophy than I have and possibly ever will. From what I remember just in Making Sense of God, he engaged Thomas Nagel, Albert Camus, Charles Taylor, Alasdair MacIntyre, and Albert Plantinga, and unlike many who do that, he even came out the other side still intelligible to the lay reader.

When I talk about him steel-manning the positions he engaged, I mean things like this. Common arguments against secularism might look like:

Any worldview that can’t offer objective grounding for morals is wrong. Secularism can’t offer objective grounding for morals, so it’s wrong.

Any worldview that can’t offer meaning or purpose to life is wrong. Secularism can’t offer meaning or purpose to life, so it’s wrong.

Any worldview that can’t offer an understanding of identity is wrong. Secularism can’t offer an understanding of identity, so it’s wrong.

And I used to think those were the bomb. I mean, absolute fire. It made me feel better about myself and my position—made me feel safe. It turns out that what makes me feel safer is knowing God closely and personally. Then, whether or not you have arguments or responses to arguments, God the King is there. He doesn’t evaporate if you lose an argument.

You also get to make better arguments, like Keller did. You see, the problem with these arguments is no secular person would read them and say “Yeah, okay, that seems right.” They would say, “That’s stupid. I do have meaning and ethics and real identity.” To which one could only say, “No you don’t, and here’s why I know better than you about your own beliefs.” And there is a long tradition of such. But instead, Keller started with the obvious: most all people have ethical codes that they take to be real and important. Of course they find meaning in life. Of course they understand identity. The real questions, which Keller asks, are what their best account of these things is, and whether those accounts are comparable to the best Jesus has to offer.

This is a quote from Making Sense of God, and I think it summarizes Keller’s own posture well:

To forgive those who have wronged us and to treat warmly those who are deeply different from us [and to steel man an argument] requires a combination of two things. We need a radical humility that in no way can assert superiority over the Other. We must not see ourselves as qualitatively better. But at the same time there can be no insecurity, for insecurity compels us to find fault and to demonize the other, to shore up our own sense of self. So that humility must proceed not from our own emptiness and valuelessness but from a deeply secure and confirmed sense of our own worth.

Of course Keller tells us where to find such humility bound to self worth. I think it’s my favorite thing he taught:

“[T]here has to be somebody whom you adore who adores you. Someone whom you cannot but praise who praises and loves you—that is the foundation of identity. The praise of the praiseworthy is above all rewards. However, if we put this power in the hands of a fallible, changeable person, it can be devastating. And if this person’s regard is based on your fallible and changeable life efforts, your self-regard will be just as fleeting and fragile. Nor can this person be someone you can lose, because then you will have lost your very self. Obviously, no human love can meet these standards. Only love of the immutable can bring tranquillity. Only the unconditional love of God will do.”

~ Making Sense of God

Some other tributes to Tim Keller I read and appreciated:

Katelyn Beaty’s article, “5 ways Tim Keller was the anti-celebrity pastor”.

Both Jake Meador’s Twitter thread, and his longer piece on Mere Orthodoxy.

Alan Noble’s Twitter thread.

A guy I didn’t know named Joel Miller’s Twitter story.

I love the personal learnings you reveal in this tribute.

Wonderfully written, beautiful account of a personal experience of Tim Keller.